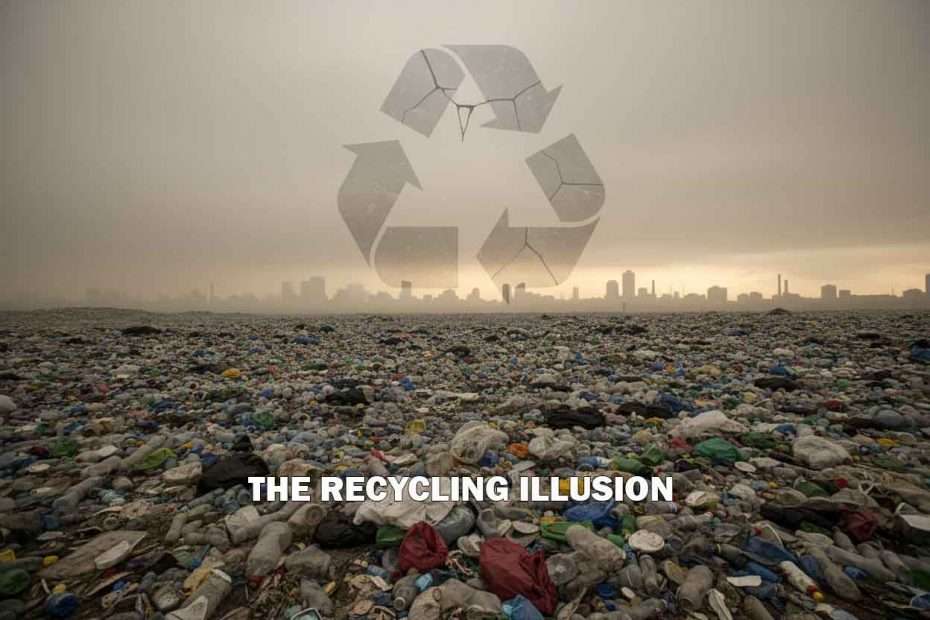

The Recycling Illusion

How Plastic Became the World’s Most Successful Greenwashing Campaign

Plastic permeates every corner of modern life. It flows through oceans, clogs rivers, washes up on beaches, fills landfills, hangs in the air, and lingers in our homes. It is in the food we eat, the water we drink, and even the bloodstreams of animals and humans alike. It is a material we have come to depend on entirely, yet it outlives every one of us, taking centuries to break down—if it ever truly does. Even then, its transformation is merely into smaller and smaller fragments: microplastics and nanoplastics that disperse invisibly into ecosystems and the human body.

Yet for decades we have been reassured that plastic waste is manageable. We’ve been handed blue bins, green arrows, and colourful messaging that tells us our bottles, tubs, and trays will be reborn into something new. The idea is seductive: that with one simple gesture—placing an item in a recycling bin—we absolve ourselves of guilt, protect the planet, and become part of a responsible, circular economy. It is, as many now argue, one of the most effective marketing campaigns ever created.

At the heart of this story is a simple but uncomfortable truth: the vast majority of the plastic we place into recycling bins is never recycled. Instead, it is landfilled, incinerated, exported, or simply mismanaged. For more than forty years, the plastics and petrochemical industries have promoted recycling not as an environmental saviour, but as a public relations tool—one designed to preserve their profits and ease growing concerns about waste.

Understanding how this happened requires revisiting an unlikely moment of history: a garbage barge in 1987 that unintentionally exposed the fragility of the recycling narrative and threatened the plastic industry’s future.

A Barge, a Bedpan, and a Worldwide Media Frenzy

In early 1987, the small town of Islip, New York, faced a straightforward yet pressing problem. Its landfill had reached capacity, leaving more than 3,000 tonnes of municipal waste with nowhere to go. To solve this, a businessman chartered a barge, loaded it with the rubbish, and set off towards North Carolina with plans to convert the waste into methane gas.

However, the scheme collapsed spectacularly when TV cameras spotted what they believed to be medical waste—including a bedpan—within the mountain of refuse. Panic spread. Rumours quickly took hold that the waste was contaminated. North Carolina refused permission for the barge to dock, setting off an extraordinary chain of rejections. Louisiana said no. Florida declined. Mexico, Belize, and the Bahamas each refused it. At one point, the Mexican Navy reportedly deployed vessels to prevent its entry.

The barge, now infamous, drifted in limbo for months. Journalists followed its journey with fascination, describing it as the “Flying Dutchman of refuse” as it wandered the Atlantic with nowhere to unload. Eventually, the waste was incinerated back in New York. The event itself was not catastrophic, but its symbolism was potent. For the first time, millions of Americans confronted a stark reality: there was simply too much rubbish, and too few places left to hide it.

For an industry already facing scrutiny, this sudden visibility of waste was a crisis. Plastic production had been booming throughout the 1980s, driven by low costs and the astounding versatility of petrochemical-based materials. But mounting pressure from environmental groups and alarmed politicians led to a surge of proposals to restrict or ban certain plastics. Stirrings of a political backlash began to threaten the industry’s long-term viability.

The plastics lobby needed a solution—not to solve the waste problem, but to manage public perception of it.

The Birth of a Deception: Creating the Illusion of Recycling

Recycling, in principle, is simple and powerful. For certain materials—aluminium, glass, some metals—it works extraordinarily well. Aluminium, for example, can be recycled indefinitely without quality loss. A discarded can may be reclaimed, processed, and returned to shop shelves in as little as two months. The economic incentives align naturally: recycling aluminium saves both energy and money.

Plastic, however, is fundamentally different. Plastics are not one material but thousands, each chemically distinct and incompatible with others. They cannot be melted together without degrading into uselessness. Even single-type plastic degrades with every recycling cycle, becoming progressively weaker and less valuable. Most importantly, recycling plastic is far more expensive than producing new plastic from fossil fuels.

Internal industry documents from the 1970s reveal that petrochemical executives understood this perfectly. They knew plastic recycling would likely never be economically viable at scale. Nevertheless, the industry recognised the power of the concept. If the public believed plastic could be recycled, opposition to its use would soften. People would continue to buy plastic products without guilt, trusting that their waste would be reincarnated rather than discarded.

In 1988, the Society of the Plastics Industry unveiled an ingenious tool to cement this belief: the Resin Identification Code. The now-familiar triangle of three arrows enclosing a number looked strikingly similar to the universal recycling symbol. To the public, it appeared to mean the product was recyclable. In reality, the symbols were never intended to indicate recyclability. They merely identified the type of resin used.

Only plastics numbered 1 (PET) and 2 (HDPE) have ever had substantial recycling markets. Plastics numbered 3 through 7—everything from PVC to polystyrene—are notoriously difficult to recycle and often economically worthless. Yet once these symbols became widespread, the public interpreted them as a seal of environmental responsibility.

To cement the illusion, industry groups lobbied state legislators to require the symbol on all plastic packaging. Thirty-six states adopted such mandates. Overnight, the recyclability symbol became ubiquitous—regardless of whether the item could actually be recycled.

It was a masterstroke of psychological engineering. Consumers, wanting to behave responsibly, would place plastic items into recycling bins even when collection systems or markets didn’t exist. This behaviour created what experts call “wishcycling”: the hopeful but misguided act of trying to recycle non-recyclable materials.

Wishcycling not only fails to recycle plastic—it actively undermines recycling systems. Contaminants jam machinery, degrade bales of material, and raise operating costs. Yet the industry’s messaging placed blame squarely on consumers. If recycling failed, it was because people sorted their rubbish incorrectly—not because the system itself was fundamentally flawed.

The Economics of Failure: Why Plastic Recycling Rarely Works

Even charity cannot overcome economics. Plastic is made from oil and gas—industries that have dramatically expanded output in recent years. The surge in fossil fuel extraction has created an oversupply of virgin plastic resin, pushing prices down. As a result, new plastic is significantly cheaper than recycled plastic.

By 2024, recycled plastic cost around $1,200 per tonne, while virgin plastic hovered at roughly $400 to $500 lower. For companies manufacturing bottles or packaging, the choice is obvious. New plastic is cleaner, clearer, stronger, and cheaper. Recycled plastic is inconsistent, contaminated, costly, and in limited supply.

In a market-driven economy, recycling cannot compete. The incentives reward continual production of new plastic rather than reuse of existing materials.

This economic reality was disguised for decades by a convenient workaround: exporting plastic waste to China. These shipments were counted as “recycled” the moment they left domestic ports, regardless of their actual fate. Much of the exported waste was burned, dumped, or abandoned, particularly in informal recycling sectors lacking infrastructure.

This system collapsed in 2018 when China enacted the National Sword policy, banning most plastic waste imports. Without an overseas destination, mountains of plastic accumulated across Western countries. Recycling facilities became overwhelmed. Many councils reduced or eliminated plastic recycling programmes. For the first time, the true scale of the recycling failure became undeniable.

In the United States, the national recycling rate for plastic fell to around 5%. Across many other developed nations, recycling rates similarly stagnated or declined.

Chemical Recycling: The Industry’s Next Big Promise

Confronted with renewed scrutiny, the plastics industry introduced a new concept that promised to solve every problem: “chemical recycling,” also branded as “advanced recycling.” Promotional materials depict an elegant loop—plastic broken down to its fundamental molecules and reconstituted into brand-new resin without quality loss. In theory, this would allow perpetual reinvention of plastic materials.

In practice, chemical recycling has largely failed to meet these promises. Most facilities rely on a process known as pyrolysis, in which plastics are heated in low-oxygen environments. Instead of returning plastic to usable raw materials, the process typically generates fuel products such as diesel or industrial oils. Burning these fuels releases harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases. The process is energy-intensive, inefficient, and costly.

Yet because the industry labels the process as “recycling,” it can claim participation in a circular economy, even when the environmental benefits are dubious or negative. These claims are often used to delay regulatory action or to justify building new plastic production plants.

Environmental organisations argue that chemical recycling is simply incineration by another name, granting the industry a green veneer while perpetuating the same patterns of overproduction.

The Psychology of Plastic: How Consumers Were Recruited

The recycling symbol does more than mislead; it manipulates. It taps into a powerful psychological mechanism known as moral licensing. When people perform an action perceived as good—such as placing a bottle in a recycling bin—they feel morally validated. This sense of virtue can then justify additional consumption. The presence of recycling infrastructure reduces the guilt associated with buying disposable plastics, encouraging continued or even increased purchasing.

This dynamic is particularly potent in modern consumer culture, where convenience and affordability are prioritised. Plastic offers unmatched convenience: lightweight, durable, hygienic, and cheap. The promise of recycling removes the ethical tension between convenience and environmental responsibility.

Thus, recycling does not merely fail to reduce plastic production—it facilitates its expansion. By assuaging guilt, it ensures demand continues uninterrupted. In effect, the consumer becomes complicit in a system that obscures its own environmental impact.

A System Designed to Fail

When viewed comprehensively, plastic recycling reveals itself less as an environmental strategy and more as a sophisticated marketing campaign engineered to protect corporate interests. The pieces fit together neatly:

• The industry knew plastic recycling was economically unviable.

• The recycling symbol was co-opted and misrepresented to imply recyclability.

• Legislation was shaped to spread the symbols as widely as possible.

• The public was encouraged to shoulder responsibility for waste.

• The failure of recycling was blamed on consumer behaviour rather than production.

• Exporting waste masked the systemic shortcomings for decades.

• New narratives such as chemical recycling now serve to delay meaningful change.

This system, established in the late twentieth century, has remained largely intact through the early twenty-first century. Despite advances in technology, policy, and environmental awareness, plastic production continues to rise, reaching record highs year after year.

What Actually Works—and What Must Change

It is important to stress that recycling itself is not inherently flawed. For certain materials—aluminium, glass, cardboard, and some metals—recycling remains highly effective and environmentally beneficial. Individuals should continue to recycle these materials wherever possible.

But plastic is a different story. The solution to plastic pollution cannot rely on recycling systems that have proven structurally incapable of managing the volume, diversity, and economics of plastic waste.

Meaningful change requires rethinking consumption patterns and production models:

• Use fewer disposable products. Reduction is far more impactful than recycling.

• Choose alternatives. Glass, aluminium, and paper often outperform plastic in recyclability and lifecycle sustainability.

• Support refillable and reusable systems. Reuse dramatically reduces waste generation.

• Pressure governments and companies. Policy and corporate action—not consumer choices alone—determine systemic outcomes.

• Demand transparency. Labelling must reflect true recyclability, not industry-crafted illusions.

Above all, consumers must recognise that the recycling symbol on plastic packaging is not a guarantee of sustainability. It is, in many cases, evidence of a decades-long attempt to shift responsibility away from producers and onto individuals.

Escaping the Plastic Trap

The plastic industry’s most powerful achievement has not been creating a useful material, but constructing a narrative that disguises the consequences of its use. The three pursuing arrows printed on plastic containers are not promises of rebirth. They are reminders of a transaction—one in which consumers unknowingly participate, believing they are contributing to environmental protection when, in reality, they are enabling an unsustainable system.

Understanding this deception is the first step in dismantling it. Only by recognising the flaws in the recycling narrative can society begin to address the underlying issue: the unchecked production of plastic and the economic structures that reward it.

The plastic trap has been carefully designed. It exploits convenience, trust, and good intentions. It ensures that even environmentally conscious people continue participating in a system that damages the planet. Escaping this trap does not require perfection, but awareness. It begins with informed choices, societal pressure, and collective demand for alternatives.

Recycling, in its current form, will not save us from plastic pollution. But acknowledging its limitations may finally open the door to solutions that can.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is plastic so much harder to recycle than materials like aluminium or glass?

Plastic is not a single material but a broad family of thousands of different polymers, each with its own chemical composition and properties. Most of these cannot be melted down and processed together without degrading into low‑quality material. Even when a single type of plastic is recycled, its quality generally diminishes with each cycle, making it progressively less useful and less valuable. By contrast, aluminium and glass can be recycled repeatedly with little or no loss in quality, and the economics of recycling them are far more favourable. As a result, plastic recycling struggles both technically and financially in ways that metals and glass do not.

2. Does the recycling symbol on plastic packaging mean the item will actually be recycled?

No. The triangle of arrows with a number in the middle—known as the Resin Identification Code—was originally introduced to identify the type of plastic resin used, not to indicate that an item is recyclable in practice. Only plastics labelled 1 (PET) and 2 (HDPE) are widely recyclable in many regions. Plastics numbered 3 to 7 are often not recycled at all due to technical and economic barriers. However, the similarity between the resin code and the universal recycling symbol has led many people to assume that any item bearing it will be recycled, which is rarely the case.

3. If plastic recycling is so limited, should people stop recycling altogether?

No. Recycling remains very effective and important for materials such as aluminium, glass, paper, and cardboard, and for certain types of plastic where collection and processing systems genuinely exist (typically plastics numbered 1 and 2). The problem is not recycling as a concept, but its misrepresentation as a comprehensive solution for plastic waste. People should continue to recycle materials that have well-functioning markets and infrastructure, while recognising that recycling alone cannot resolve the broader plastic pollution crisis.

4. What is “chemical recycling” and why is it controversial?

Chemical recycling, often marketed as “advanced recycling,” refers to technologies that aim to break plastics down into their basic chemical components, theoretically allowing them to be turned back into new plastics or other products. In practice, many of these processes rely on techniques such as pyrolysis, which often convert plastic waste into fuels like diesel or industrial oils. Burning these fuels releases greenhouse gases and other pollutants. Critics argue that calling such processes “recycling” is misleading, as they do not create a truly circular system and can be more akin to energy‑intensive incineration than genuine material recovery.

5. If recycling is not the main answer, what are the most effective ways to address plastic pollution?

The most effective strategies focus on reducing plastic use at the source rather than trying to manage waste after it has been created. This includes:

- Cutting back on single‑use and disposable plastic products.

- Choosing alternative materials such as glass, aluminium, or paper where appropriate.

- Supporting refillable, reusable, and packaging‑free systems.

- Pressuring governments and companies to introduce regulations, redesign products, and shift away from unnecessary plastic.

- Demanding clear, honest labelling about what is truly recyclable.

Ultimately, tackling plastic pollution requires systemic change in how products are designed, packaged, and sold, rather than relying primarily on consumers to sort and recycle their way out of the problem.

Bioglobe offer Organic Enzyme pollution remediation for major oil-spills, oceans and coastal waters, marinas and inland water, sewage and nitrate remediation and agriculture and brown-field sites, throughout the UK and Europe.

We have created our own Enzyme based bioremediation in our own laboratory in Cyprus and we are able to create bespoke variants for maximum efficacy.

Our team are able to identify the pollution, we then assess the problem, conduct site tests and send samples to our lab where we can create a bespoke variant, we then conduct a pilot test and proceed from there.

Our Enzyme solutions are available around the world, remediation pollution organically without any harm to the ecosystem.

For further information:

BioGlobe LTD (UK),

Phone: +44(0) 116 4736303| Email: info@bioglobe.co.uk